Rezoning concrete buildings through steel interventions

Rezoning concrete buildings through steel interventions

(An article from Rumoer 66)

By Wim Verburg (Adviesbureau voor Bouwmarketing, Rotterdam)

Old multi-storey buildings that have fallen into disuse often have a robust support structure of concrete, a rigid layout, an outdated appearance and likewise architectural performance. However, because of their built-in reserve capacity (over dimensioning and curing) they offer a solid base for rezoning and reprogramming, although it requires interventions. This article explains the convenience of a lightweight steel support.

The office buildings, post offices, co-working spaces, factories, warehouses and storage buildings that have fallen into disuse are often robust. A well-known example: The Van Nelle Fabriek, built in 1931 and rezoned in 1998, which is now accommodating several small businesses (fig. 1).

The support structures of similar buildings, built before World War II, were made of steel or concrete. Later, concrete structures gained the upper hand, because the use of steel was discouraged in the Netherlands due to the implementation of guidelines, named ‘Richtlinien zur Eisenersparnis’. Steel was predestined for other applications. When the guidelines were not followed sufficiently, a building permit could even be refused. There were also similar guidelines for wood structures. For this reason, existing economically outdated buildings are usually constructed of aesthetically appreciated concrete structures. Since they are technically still sufficient and able to be main-tained for generations, the question is: what to do with them?

Figure 1. Restored complex Van Nelle Fabriek, Rotterdam

Vision of the Chief Government Architect

Floris Alkemade has been Chief Government Architect since September 2015. He also lectures Architecture at the Academy of Architecture in Amsterdam. In the latter position, he focusses primarily on the existing built environment in the condition of Tabula Scripta (‘the described sheet’), ‘in which the context isn’t seen as a limitation, but as a chance to use the potentials of a place […] How can the existing context be reread, understood, valued and further developed.’

While designers and contractors aren’t the first to initiate such a process, they do play an essential role. After all, they are the ones who are aware of the technical possibilities and have to assess the feasibility of solutions. Achievable rezoning, determined on the basis of a business case (costs – benefits), requires smart solutions and interventions. Both for the realization of the new programme as well as for the climate and structural requirements.

Transformation possibilities

Often old buildings have to be adapted to the following programme objectives:

- Increase of square meters gross floor area (for additional exploitation)

- Adjustment of daylight entrance

- Improvement of acoustics

- Renewal of installations (outside the scope of this article)

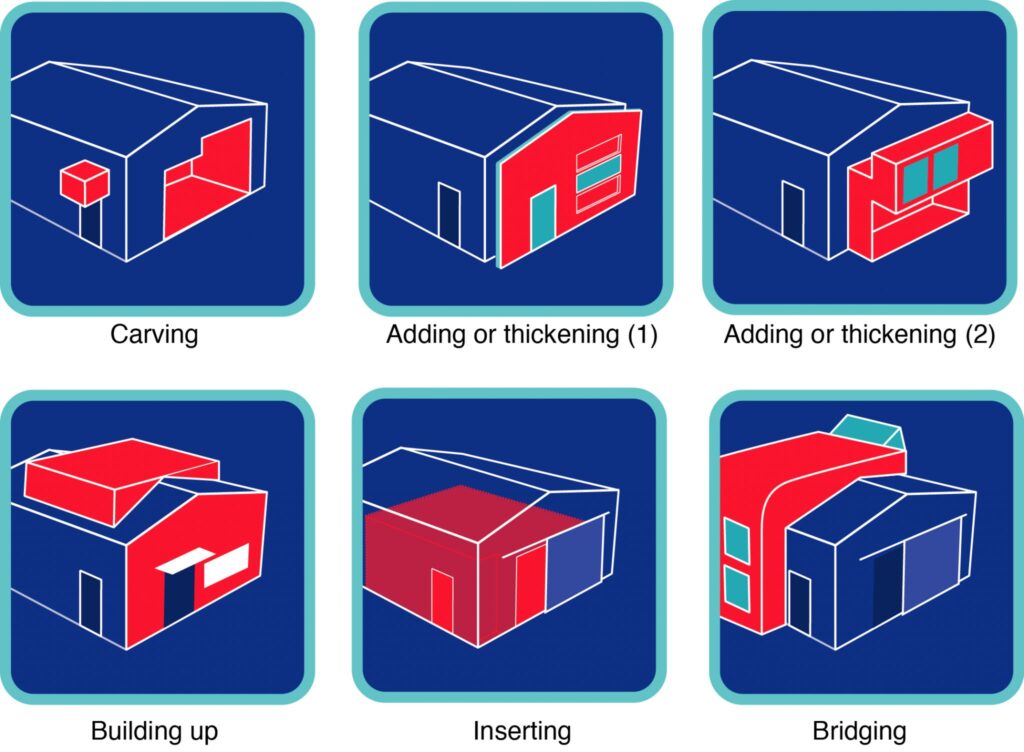

Common structural interventions (Fig. 2) for these objectives are:

- Carving (breaking open the façade);

- Adding or thickening (additional facade);

- Breaking through (walls, floors and roofs);

- Building up (additional floors on top of the building);

- Inserting (additional volumes or floors in the building);

- Bridging (an additional self-supporting building volume over the building).

Often, the retained floor load of the prior function is greater than that of the new function, for example library then versus housing now, or the concrete structure is sufficiently strong due to over dimensioning and curing. Because of this, the foundation is often also strong enough to carry the new loads. Extra square meters gross floor area has to be found in, on or by the existing building. Adapting the daylight entering requires breaking open the façade, whether or not in combination with the removal of floors and columns (so carving and breaking through). Two examples: the residential building Jobsveem in Rotterdam (fig. 3) and the stairs in the building Anton (former Philips factory in Strijp-S) in Eindhoven (fig. 4). By carving (for daylight entrance) at Jobsveem it was necessary to manage structural stability, in this case with building-high, moment-tight steel portals. At the building Anton, remarkable voids and overlooks are realised by sawing out round openings and adding steel stairs.

Figure 2. Common architectural and structural interventions

Figure 3. : Carved facades of Jobsveem, Rotterdam, with new steel stability portals

Figure 4. Re-bored floors with steel stairs in the building Anton, Eindhoven

Adapting concrete supports

In theory, any element of an existing concrete structure can be removed. But is this practical? In the national programme Industrieel Flexibel Bouwen (IFD) this is experimented with in the project Flexibele Doorbraak (2003) (fig. 5). A partition wall between dwellings of a concrete construction complex, built in the sixties, has been removed and replaced by a steel portal. From this IFD-experiment it appeared possible to remove crucial structural parts and to replace them with parts suitable to the new function and the desire for more floor space. Next to this the load distribution can also be adjusted. This approach was applied during the transformation of the Termeulen building in Rotterdam into the residential building Karel Doorman (fig. 6). The concrete structure of the former warehouse was unsupported. The horizontal loads were held by the portals, resulting in the columns being loaded with bending and normal force. The column loads at the new function and the desire for more square meters through building up would increase in such a way that they couldn’t be carried by the columns, loaded with bending and normal force. By reconstructing the unsupported construction to a supported one (through two new concrete stability cores) the columns do not contribute to the distribution of the horizontal loads and can thereby absorb a greater normal force. This made it possible to add no less than sixteen floors on top of the buildings.

Extra gross floor area

Another remarkable example of surface enlargement is the rezoning of the former Schakelgebouw 25kV (fig. 7) in the Lloyd quarter in Rotterdam, which is now a co-working space for, amongst others, graphic designers. Using steel frame construction, the gross floor area of the Schakelgebouw was enlarged by removing the old, solid façade and replacing it with a cantilevering steel-glass structure without the need of expanding or strengthening the foundation.

Steel-framed floors and structures are flexible in terms of functionality (strength and stiffness), mass (low self-weight) and pre-assembly. In the cases where there is no lifting capacity available, the system can also be completely assembled on site, delivered as a building kit. The finishing floor (sand-cement/anhydrite) can be supplied with a pump. If this wet filling is too heavy or undesirable, a dry filling can be chosen. With this, no profiled plate is used on the top side, but a wooden plate can be shot or screwed on top of the supports. The desired acoustic insulation can be obtained with one or more gypsum boards on the underside (on omega-profiles), insulation in the floor and/or a floating deck floor.

With a relatively light construction method it is often possible to add one or more floors in or on top of the building. When needed one floor can also be removed for weight reduction. Removal makes room for building up. Currently in Antwerp at a former warehouse, several layers are being removed from the top of the building to transform it into a YUST-complex (Young Urban Style) with multiple steel framed floors (fig. 8).

In the factory complex of Unilever in Rotterdam another solution is used. Office building De Brug (fig. 9) has been built over this complex on its own foundation (bridging). This execution was financially attractive, because in this way ground became vacant for the building of apartments, that would otherwise be used for a simple new office completely executed from ground level. For De Brug integrated supports were used with a high steel-plate concrete floor, due to the combination of low self-weight and comfort.

The Nieuwe Havenhuis in Amsterdam (fig. 10), designed by Zaha Hadid, is an exotic variant of ‘bridging’. On top of two enormous concrete pillars four floors are added through a heavy steel construction and steel-plate concrete floors.

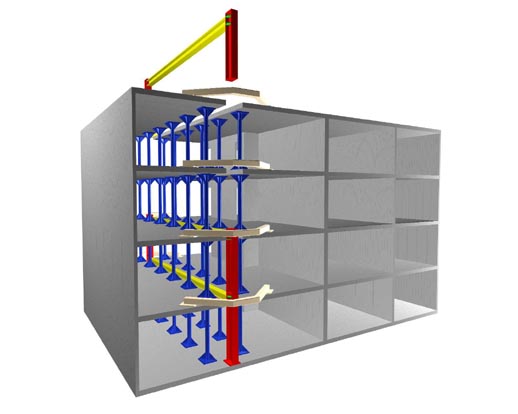

Sometimes existing buildings are so large (especially in floor height) that the extra meters can be found in the volume. An example is the transformation of the former post office station in Rotterdam. This building from 1959 was transformed into the Central Post in mid 2010. The extra meters were found by the insertion (in this case hanging) of so-called Slimline-floors (hollow steel-concrete floors). If it is feasible to place this type of floor in existing buildings, a relatively thin floor is generated in which ducts can be placed. By providing the floor with low temperature heating and high temperature cooling, less utilities are needed for heating and cooling installations.

Figure 5. Steel portal replaces concrete wall in the ‘Flexibele Doorbraak’

Figure 6. 16 extra floors with a steel structure, residential building Karel Doorman, Rotterdam

Figure 7. Former Schakelgebouw 25kV is thickened with a cantilevering steel-glass structure for more floor surface and daylight entrance

Choice of solution

The most difficult question with the transformation of locations and buildings is finding a positive business case. If found, the contractor will have to make choices for the best interventions, based on the conveyed test results. These differ per type of client. A private party will be most interested in the total cost of ownership (TCO) for the expected exploitation period. A public party will prefer the Best Price Quality Ratio, also referred to as Best Prijs Kwaliteits Verhouding in Dutch. This replaces the Economisch Meest Voordelige Inschrijving (the Economically Most Favourable Subscription), which is mainly used for infrastructural tenders.

Figure 8. In this former warehouse in Antwerp old, heavy floors are removed and then built up with more floors than before.

Figure 9. Bridge. Office building de Brug stands on top of the Unilever building in Rotterdam.

Figure 10. Het Nieuwe Havenhuis in Antwerp is an exotic bridge variant and also a landmark of the diamant city.

Bouwen met Staal (the Dutch Steel Construction Institute) informs all disciplines within the Dutch building industry – from building clients and architects to structural engineers and steel building companies – on the use of steelconstructions in building projects and civil works. The organisation develops a.o. activities in the fields of promotion, and education throughout several media like a magazine, courses, lectures and visites to projects and companies. Especially for students a chain program provides (free) products/publications (like the magazine) and activities. Amongst others.